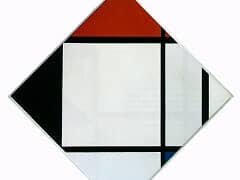

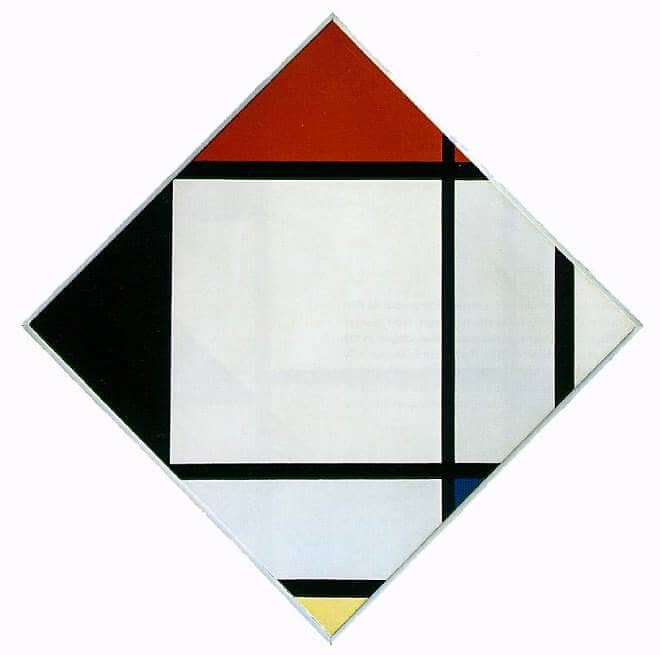

Tableau No. IV, 1925 by Piet Mondrian

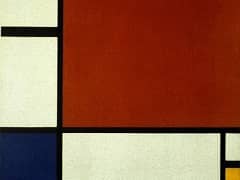

It is a commonplace about the classic phase of Mondrian's oeuvre that the artist achieves a subtle asymmetrical balance in his compositions. Much of our pleasure in engaging with these works seems to be appreciation of their balance, a balance which provokes our interest and awakens our admiration because it is so challenging. It strikes us not just as asymmetrical, which is not in itself remarkable, but as surprising, eccentric, improbable, even mysterious. The compositions are typically experienced as strong or stable yet also as dynamic, as containing the "equilibrated contrasts" at which the artist aimed. In designs so purified of representational (pictorial) significance, so resolutely flat, so deprived even of the optical space found in Jackson Pollock or de Kooning, so limited in form, color and texture, what indeed would there be to admire were it not for some extraordinary virtue of balance? The artistic challenge in such a program comes in discovering in the compositions subtlety and depth commensurate with their presumed eminence.

Further, for all their constrictive geometrical parameters - strict rectilinearity and perpendicularity - the works are full of deviations from geometrical regularity that suggest refinements of balance. The "planes" may be strictly rectangular and strictly oriented in the vertical and horizontal, but they almost always deviate from any simple proportionality. With rare exceptions what may appear squares are not in fact equal-sided. A given shape is almost never exactly repeated in a work and the large rectangles are almost never exact multiples of the smaller ones. Diagonals of the rectangles almost never carry on to the corners of other rectangles or to the corners of the support. Nothing ever stands precisely centered in the center. Further, the planes may be enclosed on all sides by the black lines or only on two or three, the free edges being bounded only by the edge of the canvas. Particularly when the canvas edge is raised above the frame, such a plane seems less confined, its comparative freedom seeming still stronger when the canvas is a diamond-shaped "lozenge," the edges of which necessarily cut the planes at a 45 degree angle.