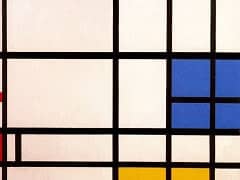

The Still Life with Gingerpot II, 1912 by Piet Mondrian

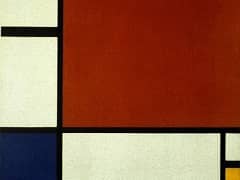

The second version of the Still Life with Gingerpot, done in the summer of 1912 after Mondrian had moved to Paris and begun to spell his name with a single "a," presents an entirely different conception. In the time that had elapsed between the two versions, Mondrian had assimilated the principles of cubism and drawn conclusions for his own art, in his characteristically thorough way.

A viewer comparing the two paintings as if inventorying merchandise might not discover a great deal of difference between the two. There is the same turquoise-colored gingerpot in the middle, with much the same sort of pans grouped around it to the right and the same sort of glasses to the left. But the role that these objects play in the painting has basically changed, marking a definite transition in Mondrian's work.

In the second version of the painting the objects have lost their character as objects and have become no more than notes in a score. Hardly anything is left of their independence, of their status as things, in the totality of the composition. This difference between the two versions comes out most clearly if one compares the foregrounds. What is in the first version was a napkin with a knife on it, sloping over the edge of the table, has become in the second a white area traversed by a diagonal. Here we have at its most evident the transformation of a factual thing into a compositional value, a process in which the thing has to give up many of its characteristic properties. Or, in other words, the artist has abstracted the rhythmic form-value of a thing from its thing - value.

In this way there is an essential difference between the first and second versions of the still life. The first version is a still life of things, the second a composition of forms. In the first version the descriptive factor still sets the tone; in the second, only the interrelations of the forms are involved. The comparison between prose and poetry could be used to describe the difference between the two versions. And indeed a fact recurs that has its parallel in the art of verse, something that should be called "visual rhyme" or "optical alliteration": the round form of the gingerpot is twice repeated in round curves in the left half of the painting, and the pans on the right have been given distinctly accentuated covers in order to balance the diagonal movement in the foreground, a diagonal that was produced in the first version by a knife and the folds of a napkin. Here Mondrian took the first step on a road by which he escaped from the domination of things.